This is an Easter reflection I did for our church a year ago. Re-posting it this Easter day. A ‘Coronavirus year’ has passed. The resurrection of Jesus continues to proclaim the victory of God over the powers of Sin and Death.

Christus ist auferstanden!

If we were physically in church this morning, retired German teacher Ian Stanton, with a mischievous smile on his face, would likely come my way and say “Christus ist auferstanden!” (Christ is risen!). I say ‘mischievous’ because he knows I will be panicking trying to remember the few words of German that he expects me to know one day a year. For the record they are “Er ist wahrhaftig auferstanden!” (He is risen indeed!).

These are days of deep uncertainty and loss. Walking around Maynooth it’s heart-breaking to read sign after sign of businesses closed. Behind those notices are stories of lost jobs, debt and fear for the future. One talks honestly about the owner’s ‘trepidation’ over the ‘big and scary’ decision to shut. I find myself praying for her and make a promise that, hopefully, when that café reopens, I’ll go and give her some business.

Walking along the canal parallel to the railway, empty trains go past. I wonder how long this is going to go on, aware there is no easy fix and multiple lockdowns could come and go for over a year or more. I think of health-care workers in MCC like Andy and Susanne on the front-line. I think of friends who have suddenly no work and no income. I wonder how many in MCC are in a similar situation. I think of other friends at high risk and pray they can stay free of infection. I think of my dad in his 90s and living at home alone and find myself strangely grateful that my mother died over a year ago and is not now stuck in a nursing home, confused, with no-one able to visit her. And if I’m honest, I also wonder about my own job.

And yet, as I enjoy the Spring air and blue sky, I know I’m deeply privileged. I have health, family, a home to live in, access to technology and food to eat. I wonder if this pandemic has caused such angst because it has hit the rich West. It has shown us to be far less safe and in control than we thought. It has made us face the possibility of sudden death. Yet millions of people in the world are only all too familiar with disease, famine and war. In Sub-Saharan Africa alone there are over 400,000 deaths annually of malaria and over 2 million new infections.

And so I think of countless Christians in the past and today who have never known the safety nets of stable employment, fair pay, a home, access to health care, physical security, food and clean water or the expectation of a long life.

And I start to wonder if this pandemic, awful as it is, is bringing more sharply into focus just how relevant and important it is that Christus ist auferstanden.

For if Christ is raised, then we can trust that our futures are in the hands of the risen Lord.

If Christ is raised, then, those in Christ through faith already have resurrection life.

If Christ is raised, then God has already won the victory over death and evil powers and that therefore Christians can rest assured that

“… neither death nor life, neither angels nor demons, neither the present nor the future, nor any powers, neither height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God that is in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Rom. 8:38-39).

And if Christ is raised, we can have a sure and certain hope that, regardless of when we die, we will share one day in Christ’s resurrection to a new life within a renewed world – one that will be gloriously free of viruses, disease and death itself.

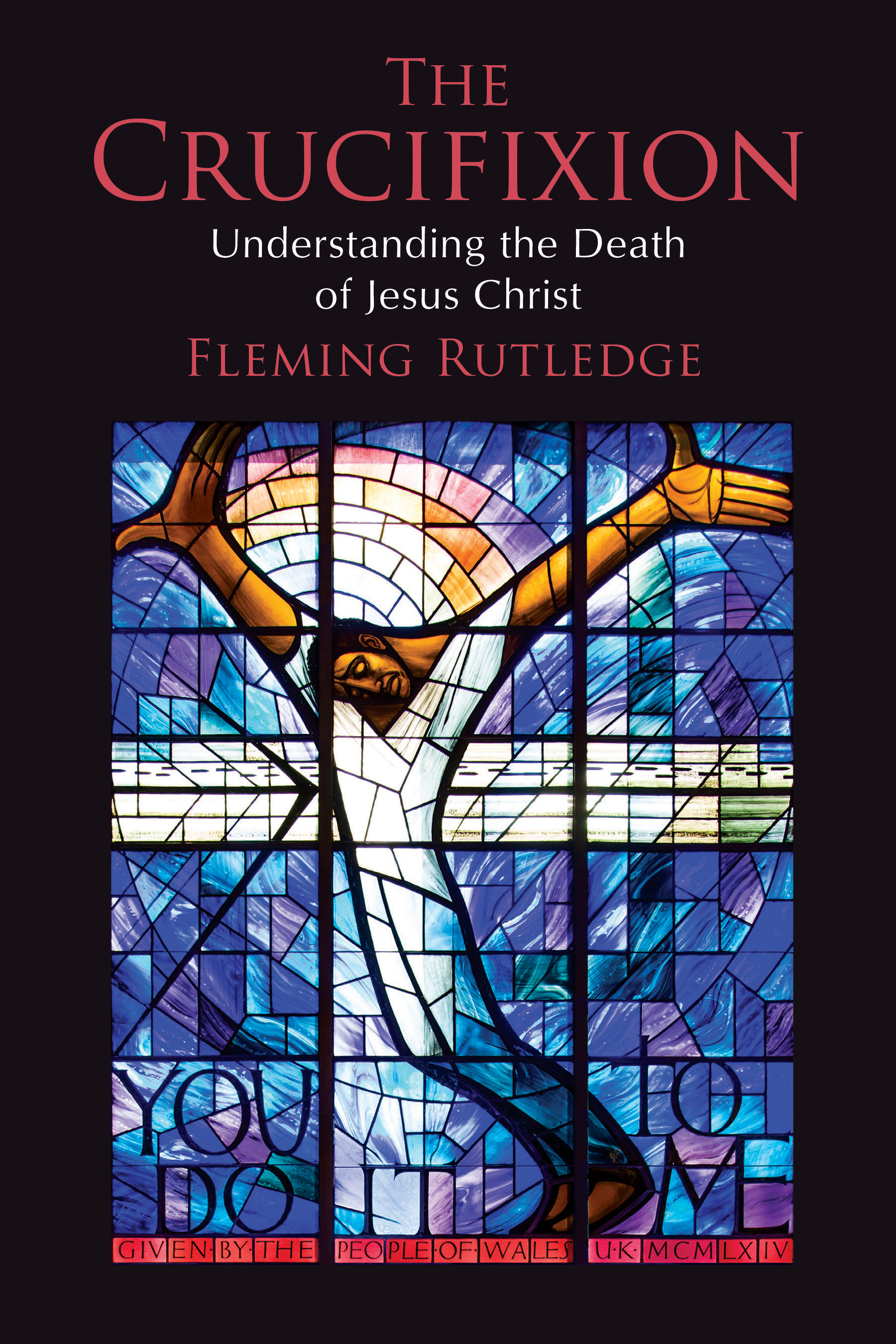

We continue our Lenten series on Fleming Rutledge’s outstanding book, The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ (2015).

We continue our Lenten series on Fleming Rutledge’s outstanding book, The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ (2015).